THE

CHANGING METAPHORS OF EDUCATION

Education,

meaning the process

of teaching and learning some form of knowledge or skill, is a concept that has

been described in metaphorical terms almost since its earliest formal

conceptualization. The terminology used to describe the value of education,

products of scholarship, individual formal aspects of an education or the

entire process itself has been based heavily on abstracting metaphor since the

time of Aristotle and Socrates, and is by no means limited to recent

developments in the English language. In fact, very few terms associated with

education have ever been particularly unabstracted,

a situation pointed out by the difficulty of describing the concept of

education in terms that do not rely heavily (if not exclusively) on metaphor.

The study of

literature, being the realm in which the use of language has traditionally been

most immediately explored (and the “mother” department of linguistics in many

cases) in higher education is especially susceptible to metaphorical

abstraction of its products and processes, a phenomenon which this paper will

argue is undergoing a change away from a paradigm based on a metaphors of

guidance and initiation towards metaphors based on expansion and discovery. To

do so, I will begin with an overview of some traditional and historical notions

about the role of education and how those ideas translate themselves into

metaphorical schema. Then, using some examples taken from presentation and

session titles from the 1998 Modern Language Association meeting in

As an opening

salvo against the idea that academic jargon is somehow “worse” or more

pronounced in the 1990s is contained within Peter Burke's excellent 1995 piece

entitled “The Jargon of the Schools,” in which he takes the reader through the

history of complaints about the abstracted (and potentially meaningless) nature

of the language of education. In his introductory discussion of the subject,

Burke writes:

The phenomenon of academic jargon...is

sometimes explained by the over-specialization and competition of the modern

academic world, the proliferation of new disciplines, journals and university

departments and the consequent need for individuals and groups to mark out and

defend their intellectual territory and to distinguish themselves from their

competitors.[...]

Such

relatively new developments may encourage jargon, but the phenomenon—or the

accusation anyway--goes back at least as far as the ancient world.1

He then goes on to discuss, in great

detail, the barbs hurled against linguistic innovations in academic discourse

by writers and thinkers like Plato (who railed against the original Sophists),

Epicurus, Seneca, Petrarch, Erasmus, Luther, Calvin, Hobbes, Webster, Locke and

others up to the 1960s. Burke's essay points out an important, practical

linking theme of the attacks against “the vainglory of syllogizing sophistry”2

or “strange and barbarous words”3: “Hobbes's purpose was, of course

to undermine...the discourse of the 'School-Divines', as he called them—in

other words, the theologians whose obscure political terminology, so Hobbes

claimed, was responsible for the recent civil war.”4 The complaints

against the language stem from a larger complaint against the philosophy of

those who use the particular language in question. If one looks at the main

trunk of backlash against current academic neologisms in literature, it is

possible to see a similar desire to “undermine the discourse” of groups who are

attempting to assert a place within the study of literature that has

traditionally been denied them.

R. K Elliott,

in his essay “Metaphor, Imagination and Conceptions of Imagination” discusses

some of the central metaphorical associations that have traditionally been made

with education, discussing several of them in light of their historical

origins. Some of the most common that he picks out are the following:

“education as formation or production; as preparation or apprenticeship; as

initiation; as guidance; as growth; as liberation.”5 About these he

comments that “Each presupposes that education has a point or purpose, and each

is normative in character, indicating what education ought to be by seeming to

state, incompletely, what it essentially is.”6 Even a cursory glance

at a thesaurus yields a panoply of phrases synonymous with education that fit

into Elliott’s categories. A number of these are based on ontological metaphors

that substantiate education (as in “My education in English literature

qualifies me for this job”) or make education into a quantifiable and

qualifiable entity (as in “I received a first-rate education from Harvard”).

Others are based on substantive metaphor that equates education with the

process of teaching and learning (as in “Elementary education is very different

today than it was twenty years ago”).

For example,

the words “edification” (from Latin aedificare,

“making of a temple”) and “instruction” (Latin root struere, meaning “pile up' or “build”) are derived from Latin

metaphors within the paradigm of formation or production. They are certainly

not alone in this status as English has derived a host of other phrases that

commodify and physicalize the concept of education—”building one's future

[through education]” and “making something [better] of one's self” spring

immediately to mind. Especially as the perceived role of colleges and

universities has evolved (for many administrators, educators and students) from

primarily being “the methodological discovery and teaching of truths about

serious and important things”7 to providing an atmosphere for

advanced vocational training of all sorts, the idea of students becoming

“products” of a school has become more commonplace. Likewise, the ideas

expressed by those students are in turn viewed as “products” themselves

(witness the phrase “intellectual property,” which seems to physicalize ideas).

This schema is

not limited to concepts of education in English. The predominant Russian word

for education (“obrazovanie”)

contains the root “obraz-,” which

alternately can mean shape, form, image, way, etc., thereby placing it also

into the “education is formation” schema. The German phrases “bildung” (which, in addition to

“education” can also mean “formation,” “development” or “creation”) and “ausbildung” (often translated as

“training” but more accurately rendered as a specific kind of education, like “bibliotheks-ausbildung” or “librarian's

training”) also work in this model, stemming from the root “bild” or picture. The metaphorical

extension in bildung involves

changing ideas into a formal representation (a picture) of knowledge.

Likewise, the

metaphorical schema of preparation seems to be one that has no end of

metaphorical expressions occurring in English, such as “training,” “exercise,”

“discipline,” or “familiarization”. Each of these expressions in some way

involves introducing a pupil to a concept or skill and making it readily

accessible to him/her by repeated, possibly rigorous contact. Without resorting

to the too-easy joke that this vocabulary explains the repetitive and “by rote”

nature of much traditional education, it is true that these metaphors have

fallen somewhat out of fashion as the client/provider relationship between

pupil and teacher has begun to replace the more medieval notion of novice/adept

(or novice/guru if the more recent parlance of the 1960s is preferable). I do

not wish to make an assertion of superiority of any kind for this latter model,

only to point out that the metaphorical language of the process has followed

along with the redefinition (again using metaphor) of the teacher/student

interaction.

However,

the central metaphor of traditional education is almost certainly the idea of

leading a student down a particular (presumably true) path to knowledge. The

word “education” itself contains this basic meaning (the English word “duct”

springs from the same Latin root as education, ducere, which means “to lead”) and the list of derived metaphors

from this idea is lengthy. From the simple one-word metaphors like “direction,”

“guidance,” “tutelage” or “tutoring” (both of which derive from the Latin verb

for “watching [over]”) to the more elaborate conceptions of “showing/pointing

out/teaching/demonstrating the [proper] way,” educational metaphor is filled

with instances in which a teacher is presented as a Vergil figure corresponding

to the student's role as Dante. Along with this follows the concept of

“enlightenment” as a metaphor for education, since one must presumably “shed

light” on the “proper way” as one leads another down it. Conflated images of

illumination and education date back to ancient times and even provide

historians with a catchy name for the period of European history associated

most closely with the rise of humanist education, i.e. the Enlightenment.

Finally, this metaphor also resembles the “education as initiation” schema,

since leading someone down a path to a desired and normative goal is a fitting

description not only for education in the “guidance” metaphorical schema, but

initiation processes in general.

Reference

to the tenth edition of the Merriam-Webster's

Collegiate Dictionary demonstrates the ubiquity of these three concepts in

the definition of education:

ed·u·cate \e-jƏ-kāt\ vt (15c) 1 a: to provide schooling for b:

to train by formal instruction and supervised practice especially in a skill,

trade, or profession; 2 a: to develop mentally, morally, or

aesthetically especially by instruction b:

to provide with information: INFORM;

3: to persuade or condition

to feel, believe, or act in a desired way. 8

Definition 1 (especially 1b) fits into

the schema of “education as preparation,” whereas definitions 2a and 2b both

are examples of “education as formation.” However, it is in definition 3 that

the root of the whole argument about the nature and language of education takes

center stage. The conflict between differing conceptions of “the desired way”

(the “duct” down which the student is to be led and what he/she will find at

the end of it) is the direct cause of criticism of the language, a situation

which is in turn engendered by conflict between the different philosophies of

higher education that exist today. Elliott writes of the established

educational metaphors:

When we ask concerning the meaning of

these metaphors, their incompleteness and therefore ambiguity becomes apparent.

If education is preparation, for example, it may be preparation for life, or

for work, or for war, or for prayer and the love of one's neighbor.... Every

education might claim to be guidance, but different educational theories have

different ideas about what counts as guidance.... It is not because of their

versatility that they have become prominent in educational discourse, however,

so much as by virtue of their connection with certain well-known theories of

education, for as well as having a free and untrammeled use, they are also used

in such a way that their interpretation is bound to the theory (or type of

theory) of education with which they are most closely associated, and to which,

in some cases, they might be said to belong.9

The remainder of this paper will look

at how just the titles of papers and sessions from last year's MLA conference

are evidence of significant motion toward the “education as guidance [towards a

specific goal]” away from the “education as initiation [into a profession or

other group]” model. Those who use this parlance represent a concept of

education that involves expansion of (rather than simply achievement of) the

“goal” or the “group” of these two metaphorical models.

If

education is understood as initiation, one must certainly ask the question of

what exactly one is being initiated into. In the case of literary study, one is

initiated into a group of people who are familiar with what has come to be

known metaphorically (of course) as “the literary canon.” This term is itself

derived from ecclesiastical law and its etymology dates even further back to

the Greek word, kanōn, meaning “rule.” If we then interpret this idea of being

initiated into the literary canon as learning to follow the “rule” of

literature, it is necessary to look at what that “rule” has generally implied.

Up until the early 1960s, the canon was generally a very white, male and

European collection of writers running the temporal gamut from roughly Beowulf to late Modernist writing.

Literature produced by women, minorities, non-Europeans and other marginalized

groups was generally de-emphasized or excluded entirely, either through social

convention, censorship or professional collusion. As literary study has begun

to expand in order to include the writing of previously excluded groups, it has

had to expand not only its critical vocabulary (hence, feminist criticism,

“queer theory,” post-colonialism, et al.) but also its metaphorical approach to

how it perceives its mission and process. My purpose here is not to take sides

in the issue of whether this expansion of the canon is good or bad, but rather

to discuss the ways in which the various sides of the debate can be identified

merely by examining the language that they use.

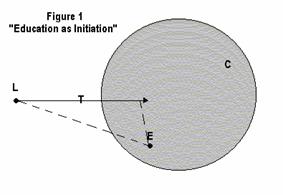

With

the expansion of the canon to include any writer deemed to have merit (and

perhaps with the subsequent expansion, courtesy of deconstructionist and new

historicist criticism, to include any writer period) comes an attendant destabilization

of the idea of a firm “rule” about which one is educated in order to be

initiated into the profession of literary study. The “education as initiation”

model is an inward-moving metaphor (see fig. 1 below) in which the learner (L)

moves along a trajectory (T) demonstrated by the educator (E) until he/she

reaches the bounded area of knowledge, or canon (C), into which he/she is to be

initiated.

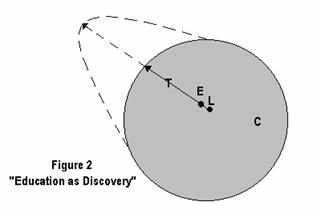

On the other

hand, the newer concept involves a radical reshaping of the whole metaphorical

framework (see fig. 2). The learner and the educator are much more closely

linked, although the educator still takes on something of a facilitating role.

The trajectory along which they move is now outwardly oriented, with its

leading edge pushing on the boundary of the canon, which now encompasses both

communal, professional knowledge and

personal knowledge of the learner and educator. The bounded area expands as the

trajector pushes on it and surrounds more of the domain area, in this case the

entire possible corpus of literature. The learner and educator “ride” the

trajector together as it expands to include more and more works within its

canon. I will call this metaphorical schema “education as

discovery

[or recovery] and expansion.”

Some

examples of this newer attitude towards the teaching and study of literature

can be clearly seen in some of the following titles (unless otherwise noted,

the titles are individual paper titles) from the MLA convention program:

“Technology, Distance and Collaboration: Problems with Expanding Networked

Pedagogies;”10 “The Computer as Catalyst: Where Do Second Language

Acquisition Research, Cultural Studies and the Less Commonly Taught Languages

Fit In?;”11 “To Transvest, but not to Transgress: Avoiding Deviance

in the Decameron;”12

“Subverting the Norms” (panel title);13 “Border Theory in the Age of

Globalization;”14 “Tightening Belts, Broadening Horizons;”15

“Mainstreaming Mr. Orton;”16 “Teaching Tolerance: Combating Bigotry

in the College Classroom;”17 “Postcolonial Gothic and the New World

Disorder: Crossing Borders of Space and Time in Margaret Atwood’s The Robber Bride;”18 “Conflict, Cooperation, Convergence: A

Roundtable on the Academic and the Nonacademic in Gay, Lesbian and Queer Print

Culture” (panel title);19 “No Sage on the Stage: Collaborating with

Graduate Students in Teaching Literature;”20 “Reorient(aliz)ing the Renaissance” (panel

title);21 “The Globalization of ‘Culture’: Perspectives from Three

Fields” (panel title);22 “Evaluating without Assimilating;”23 “Doctors Without Borders: Professing an

Imagined Community of Written English Language;”24 “Recovering Lost

Poetry by Nineteenth-Century American Women: Rethinking Why Women Wrote;”25

“Tolerating Theory;”26 “The Moral and Social Ramifications of the

Reelitification of Public Higher Education;”27 “Unearthing the

Atwood Canon” (panel title);28 “The ‘Deviant’ Classroom: A

Roundtable Discussion on Inclusive Higher Education;”29 “Finding a

Place for Kristeva and Transference Love in Pedagogy;”30 “Promoting

Multicultural Education through Creative Writing: Crossing Cultures and

Genders;”31 “Bridging the Gap: A Comparative Methodology for Third

World Literary Criticism;”32 “Reading Our (Br)Others;”33

“Become the ‘Other’: China’s Challenge to American Teachers.”34

These are only a few examples (after all there are several thousand

presentations annually at MLA) and only represent the “education as discovery”

model. There are an equal, if not greater, number of titles that reflect the

traditional conception of what literary scholarship is intended to accomplish.

However, examination of the language used in this data set does lead to some

preliminary conclusions.

An

admission of possible problems with this analysis is in order. The data I am

using is not, in the strictest sense, a vocabulary of educational practice in

the way that most of the accepted terms that illustrate the traditional

metaphorical schema are. Rather, the titles I have chosen to include from the

MLA represent some of the results of applying a different educational ideology

to the available raw material (literary texts). In essence, this is a secondary

step, but I believe it to be a logical argument that the product of scholarship

is necessarily shaped, if not defined, by the primary metaphorical conception of

scholarship and education. For example, if I conceive of my education as a

“collaborative (between myself and an educator) unearthing of ideas beyond the border of my knowledge” it

seems logical to me to believe that I will express my findings about literature

in language that reflects this central metaphor. Alternately, if I perceive of

my education as “being guided by someone else into an established body of knowledge,” there is an inherent

contradiction between my conception and the notions of “transgressing,”

“discovering,” “unearthing,” “bridging a gap,” “finding a place for,” or any of

the other spatial metaphors used in the examples above. For example, if one

believes the writing of Venedikt Erofeev or Wole Soyinka or Thomas Pynchon or

Kathy Acker not to be a part of (or to be outside)

the canon, then there is really no question of “finding a place” in the canon for their work. Such an

action is by definition impossible if one’s canon is rigid and definitively

bounded.

The

terms found in the examples from the MLA meeting demonstrate a distinct

rejection of the ideas that only what is inside

the canon is worthy of examination (i.e. teaching, since all these papers

presumably are part of educating the body of literary scholars). Words and

phrases such as “the other,” “borders” (often paired with “crossings”),

“transgressions,” “tolerance” and any of the myriad “re-“ phrases

(“rethinking,” “revisioning,” “reexamining,” “revisiting,” etc.) all demand

validity for perspectives or subject matter that are rejected by traditional

ideas of canon. These ideas are often explicitly named by their proponents as

“deviant,” “queer,” “alternative,” or “outside,” words that associate them with

notions of exclusion from the norm. The fact that each of these four words has

also taken on a figurative and metaphorical gravity in critical discourse

should not come as much of a surprise given this divergence of perception.

Notably, most of the terminology used by these scholars’ titles employs

physical metaphor to describe the status of their work in relation to the

canon. All of the articles, by dint of their very existence as products of

literary scholars (those already initiated), implicitly demand recognition as

part of the canon. However, their subject matter is often excluded from the

canon and their language reflects this exclusion by using physical metaphor to

situate it outside the traditional bounded area of literary study. The

necessity of this contemporaneous insider/outsider scholarly stance (and

resulting language) demonstrates that resistance to the ideas represented is

alive and well. This resistance is often represented by the scornful, almost

Hobbesian denunciations of the language (and, by extension, the ideas) of those

who discuss non-canonical works, writers or critical approaches (cf. Lutz or

Sokal and Bricmont,35 although neither deals explicitly with

literary study).

When the ideas

of being an “insider” writing about something “outside” are conflated, the

schema of education represented by figure 2 is brought into play. No longer is

the canon rigid and no longer is the motion of either educator or learner

inward. Rather any person that can lay a claim to being an educator or a

learner within the field is able to push the boundary of the canon outward. Whether

or not this model holds in the case of a complete novice writing in an entirely

non-canonical way about literature is unclear, as there are not many instances

of this happening. I suspect there is still some kind of authoritative status

required to be able to start pushing at the boundaries, but it may be as simple

as collaborating with someone else of authority. This leads to a sort of

infinite regression of authority that I do not have the answers for, but is

ultimately no less satisfactory an answer than that given by the canon-keepers,

whose standards are equally (if not more) obscure.

Ultimately,

the “education as initiation” schema implies a rigid canon, since the

conception of education which it embodies implies a unidirectional flow of

established knowledge from teacher (member) to learner (initiate). The

expansion of the canon requires the consent of the membership in this

conception, a process that the MLA perfectly demonstrates is neither quick nor

easy. As the concept of “co-learners” or “collaborative education” begins to

become more accepted, the language of educational processes and products is

likely to follow suit. A glance through professional journals of education

(especially those involving technology, like On the Horizon) demonstrates the vogue that these terms are gaining

in current theory. I will leave it both to time and to others more qualified to

determine whether or not this is a good thing, but the change in metaphor has

already arrived.

NOTES

1. Peter Burke, “The Jargon of the Schools,” in Languages and Jargons: Contributions to a Social History of Language,

ed. by Peter Burke and Roy Porter (Cambridge, England: Polity Press, 1995), 22.

2. John Webster, quoted in Burke, 32.

3. Thomas Hobbes, quoted in Burke, 31.

4. Burke, 23.

5. R. K. Elliott, “Metaphor, Imagination and Conceptions of Education,”

in Metaphors of Education, ed. by

William Taylor (London: Heinemann, 1984), 38.

6. Elliott, 38-39.

7. Edward Shils, The Calling of

Education: The Academic Ethic and Other Essays on Higher Education

(Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1997), 3.

8. Merriam-Webster's Collegiate

Dictionary, 10th ed. (Springfield,

MA: Merriam-Webster, 1997), 367.

9. Elliott, 39-40.

10. Modern Language Association. “Program of the 1998 Convention, San

Francisco, California, 27-30 December,” PMLA:

Publications of the Modern Language Association 113 (1998), 1314.

11. Ibid., 1315.

12. Ibid., 1317.

13. Ibid., 1320.

14. Ibid., 1324.

15. Ibid., 1325.

16. Ibid., 1325.

17. Ibid., 1326.

18. Ibid., 1327.

19. Ibid., 1327.

20. Ibid., 1344.

21. Ibid., 1346.

22. Ibid., 1356.

23. Ibid., 1364.

24. Ibid., 1365.

25. Ibid., 1381.

26. Ibid., 1383.

27. Ibid., 1385.

28. Ibid., 1385.

29. Ibid., 1399.

30. Ibid., 1401.

31. Ibid., 1402.

32. Ibid., 1403.

33. Ibid., 1404.

34. Ibid., 1406.

35. Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont, Fashionable

Nonsense: Postmodern Intellectuals' Abuse of Science (New York: Picador

USA, 1998).